Amelia Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, at her grandparent's home in Atchison, Kansas, a small town overlooking the Missouri River. She spent much of her childhood in Atchison with her grandparents and attended private schools there. Amelia's father, Edwin Earhart, worked with the Rock Island Railroad as a claims manager. When he was transferred, the family moved to Des Moines, Iowa. It was at the Iowa State Fair that Amelia saw her first airplane. She described it as "a thing of rusty wire and wood and not at all interesting". Keep in mind that this was only five years after the famous Wright Brother's flight at Kitty Hawk. After a series of moves, Amelia's parents separated and Amelia, her sister, Muriel, and their mother moved to the Chicago area where the two sisters were enrolled at Hyde Park High School. Amelia graduated in 1916. In her senior class yearbook, her portrait was captioned, "the girl in brown who walks alone."

While Muriel went to Saint Margaret's School in Toronto to begin studies to enter the teaching field, Amelia enrolled in Orgontz School, a college preparatory school, in Philadelphia. Amelia sought out challenging authors such as Shaw and Dostoyevsky and saw reading as an adventure. She enjoyed her studies and excelled in her class assignments. However, she chafed at the limitations put upon her to study what was suitable for young ladies. Her leadership qualities began to emerge and she was elected vice president of her class.

Duringthe Christmas holidays of 1917, Amelia visited Muriel in Toronto. Canada had already been engaged in World War I for years and it was here that Amelia saw the shocking effects of war. At this point, U. S. involvement was too new to have produced the types of casualties she saw in Toronto.

She returned to Orgontz as scheduled, but soon left school despite parental opposition to return to Toronto to train to become a nurses' aide. She worked with the V. A. D. (Volunteer Aid Detachment) at Spadina Hospital in Toronto until Armistice in November of 1918. Her duties ranged from serving meals and scrubbing floors to playing tennis with recovering patients. She also worked in the pharmacy because of her strong background in chemistry.

Not long after Armistice, Amelia succumbed to the influenza epidemic in December of 1918. The long hours and tiresome work had taken their toll and it was nearly a year before she recovered, leaving her with a recurring sinus problem that plagued her much of her life. In the fall of 1919, Amelia enrolled at Columbia to study premed."I had acquired a yen for medicine and I planned to fit myself for such a career..." It took her only a few months to learn that she was not cut out to be a physician, although she excelled at her studies. She then considered studying to do medical research. Earlier that year, Amelia's parents reconciled. With considerable pressure from her parents, Amelia moved with them to California in the spring of 1920.

When Amelia moved to California, she was 23 years old, tall and slim, with waist length hair. Her parents had reunited and her father had already set up a legal practice. Shortly after her arrival, Edwin took her to an aerial meet at Daugherty Field in Long Beach. She wrote of the meet, "The interest aroused in me in Toronto led me to all the air circuses in the vicinity." She also wrote that she might like to fly.

She asked her father to inquire about a flight and the cost of flying lessons and was booked for a flight the very next day at Rogers Field, an open space on Wilshire Boulevard. The cost was $10 for a 10 minute flight with Frank Hawks. Hawks later became a high speed flight record breaker. Amelia commented of her father, "I am sure he thought that one ride would be enough for me." But she knew, "As soon as we left the ground I knew I myself had to fly."

Amelia would have sat in the front seat of an open cockpit Canuck or Jenny with goggles and a leather helmet. The pilot flew from the rear seat. The ten minute flight probably circled downtown Los Angeles and then included a spectacular sweep over the Pacific with a breathtaking view of Catalina Island. In December of 1920, the skies were probably smooth and clear.

That evening she told her parents,

I think I'd like to fly.

The family did not take her inspiration to fly seriously. She made her own inquiries and found a woman pilot to instruct her. The female flight instructor quieted any possible objections of impropriety made by her parents. She hired Anita Snook, also known as 'Neta' or 'Snooky,' for $500 for the first 12 hours of instruction. Neta was based out of Kinner Field, in the South Gate area of Los Angeles near Huntington Park. The field was owned by Bert Kinner, who was in the process of building a small biplane prototype called the 'Kinner Airster.' He was convinced that soon every family in America would own one, just as they owned an automobile.

Neta's recollection of her first encounter with Amelia Earhart was as:

"...a tall, slender young lady and a elderly man approaching. She was wearing a brown suit, plain but of good cut. Her hair was braided and neatly coiled around her head, there was a light scarf around her neck and she carried gloves...

"I'm Amelia Earhart and this is my father... I want to learn to fly and I understand you teach students... Will you teach me?'"

The two women became immediate friends. For the first two months, most of Amelia's instruction was ground based, but she managed to log in nearly four hours of air time. She read books on aerodynamics at the library, helped in her father's office, worked at the telephone company and several other odd jobs to pay for her flight instruction. After six months, she had become a reasonably accomplished pilot. Yet Neta felt that she lacked the instincts to become a 'natural' - a really great pilot.

At this point, Amelia insisted on buying one of the Kinner Airsters against Neta's advice. Neta thought that there were some inherent problems with the airplane and that it was not a plane for beginners. It was underpowered, lacked stability and the engine was often unreliable. Amelia liked the aircraft because it was air cooled, which meant it had a simpler system and it weighed less. She was able to pick it up herself by the tail and move it around without using a dolly or having a man to help her. On July 24th, 1922 (her 25th birthday), she purchased the prototype Kinner Airster for $2000 and named it "The Canary" because of the bright chromium yellow paint job.

At this time there were less than 100 female pilots in the United States.

One of the more memorable events for any pilot is the first 'unscheduled landing.' Neta records Amelia's first crash as follows:

"A grove of Eucalyptus trees grew at the far end of the runway. On takeoff, the Kinner Airster didn't gain altitude fast enough to quite clear those trees--that pesky oil-clogged third cylinder. There was nothing to do. To nose down for more flying speed meant slamming into the trees. To pull up meant a stall. Amelia pulled up--I would have done the same--the plane stalled [and] on ground contact the propeller was broken and the landing gear damaged. That was Amelia's first crash. She [had bitten] her tongue but had the presence of mind to cut the switch. When I looked back, she was powdering her nose. "We have to look nice when the reporters come," she reminded me.

Even minor aircraft crashes were headlines at this point in aviation history.

After the crash, Amelia also took extra instruction from John 'Monte' Montejo, a pilot more experienced with the Airster. She wanted to learn some stunting to know how to get herself out of unexpected circumstances she might encounter in the air.

Finally, she felt ready to solo. She had to abort her first attempt due to a broken shock absorber. On the second attempt, her takeoff was unremarkable, she took her Airster to 5,000 feet and finished with a

"thoroughly rotten landing."

She celebrated her success with a new leather flying coat. Because of the obvious newness of the coat, she was subjected to much teasing. So she aged her coat by sleeping in it and staining it with a little aircraft oil. Now she looked the part, but her piloting skills were still in doubt.

Although financial constraints forced Amelia to work a variety of jobs to continue flying, she was able to gain valuable experience as a pilot. In the summer of 1922 she was featured in the Los Angeles Examiner in an interview where she stated that she would like to fly across the continent. By October, her flying skills had improved to the point that she engaged in several record breaking activities. She began by setting the women's altitude record at 14,000 feet. This record, however, lasted only a few weeks. Some weeks later, she attempted to regain her record even though the weather conditions were less than perfect. At 10,000 feet she encountered thick clouds with snow, sleet and zero visibility. Because her flight experience had all been in the Los Angeles basin, it was very unlikely that she was prepared to fly in these conditions. After reaching the desired altitude, she stated that she put her plane into a deliberate spin as the quickest way out of the situation. In the meantime, the ceiling had deteriorated from 10,000 feet to just a few thousand feet, leaving very little distance to recover from the spin.

In March of 1923, she participated as one of the advertised attractions in an Air Rodeo at the Glendale Airport. She was billed as part of the "Ladies Sportsplane Special featuring Miss Amelia Earhart flying a Kinner Airster and Miss Andree Pyre flying a Sport Farman."

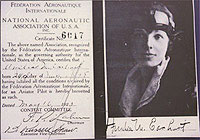

On May 16, 1923, Amelia was granted her flying certificate from the FAI, Federation Aeronautique Internacionale. Although flying licenses were not required at this time, the certificate was necessary in order to make attempts on FAI held records.

It was at this point in time that the Earhart family finances were in critical state and Amelia felt obligated to help. She reluctantly sold her Kinner Airster to a young man who had done some flying during the war. He immediately got a friend to go along with him on his first flight in his new purchase. At nearly one hundred feet, the pilot began stunting. As all the bystanders watched in horror, the plane slipped off a vertical bank and nosed into the ground, killing pilot and passenger. Her 'Canary' was gone.

The Earhart family was in shambles by this time and by late spring of 1924, Edwin filed for an uncontested divorce. Amelia, her mother and Muriel decided to move to Massachusetts. Muriel went ahead by train to begin summer classes at Harvard and established a home near Boston. Amelia and her mother remained behind for a time.

It was at this time that Amelia bought her Kissel. She did not like the idea of traveling by train across the country and thought that the car excursion would be second only to her dream of flying across the continent. She often called her car the "Kizzle," but later referred to it as the "Yellow Peril." The name seemed quite apt. Those who knew her said she was quite the speedster around town. Amelia confessed that she learned how to fly before she learned how to drive a "motorcar."

1923 Kissel Speedster

Model 45 "Goldbug"

6 cyl. -- 41 hp

Owned by Amelia Earhart

1924-1929

Purchased by the Forney Museum 1961

The drawers in front of the back fender pull out and become a passenger seat with fold up back and arm rests. Imagine the ride!

Amelia and her mother left Los Angeles for Boston in May 1924, traveling through Sequoia, Yosemite, Lake Louise and Banff. They drove across Canada and arrived in Boston 6 weeks later. Considering the condition of roads at that time and the rarity of mechanical help, especially in the more remote areas, this was a daring adventure covering 7,000 miles and covering the car with tourist stickers. Cross-continental travel by automobile was still a novelty, so Amelia and her mother were continually stopped by people and asked many questions. She found the bright yellow car, unremarkable in Los Angeles, to be an attention drawer across the country. "The fact that my roadster was a cheerful canary color may have caused some of the excitement. It had been modest enough in California, but was a little outspoken for Boston, I found."

In Boston, Amelia worked as a social worker for the Denison House. She often taught English and other subjects to foreign born men and women. She also kept in contact with local pilots and joined the Boston chapter of the National Aeronautic Association and was able to fly on occasion. At this time, to the distress of some of her more stuffy relatives, her name began to appear in print. Amelia began to realize the value of publicity. There was much attention when she 'bombed' the city with leaflets that advertised a fundraising event. When the Boston Globe interviewed her in June of 1927, she took advantage of the occasion to promote aviation, especially for women. After this article, she was often the subject of articles where she was described as "one of the best women pilots in the United States.

In April 1928, Amelia's life changed forever. She answered a phone call in her office from Captain H. H. Riley, who asked her to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic.

Next PageSome of the pictures and information were obtained from:Twenty Hours, Forty Minutes and The Sound Of Wings

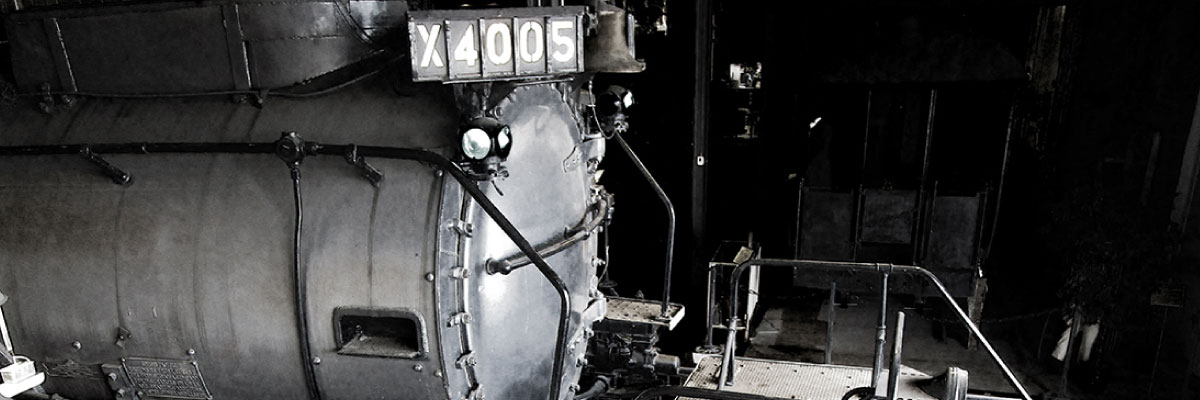

The Moffat Modeler's N-Scale Model Train Layout

The Timme Motorcycle Collection

Come and see some incredible vintage Indian, Honda & other rare motorcycles! *Exhibits subject to change without notice*

Visit our Gallery

Make sure to visit our gallery. Our gallery features various die-cast models, art, and other artifacts related to transportation.